Kilder med arbejdsspørgsmål om Gulag

Find kilder, opgaver og arbejdsspørgsmål til 'Gulag-fangelejre og deportationer'.

Fanger i Gulag

Arbejsspørgsmål

1.Hvordan kan det være problematisk at anvende tal, som kun angiver fangeantallet for en bestemt dato, hvert år?

2.Hvad kan være problemet ved at bruge det hemmelige politis egne tal?

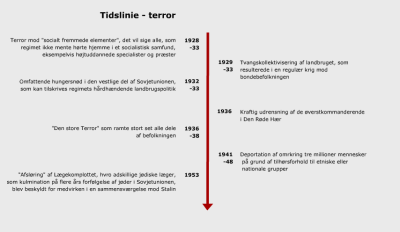

3.Kan du se nogen sammenhæng mellem antallet af fanger og de forskellige terrorbølger, som fremgår af Tidslinie - terror. Hvordan?

Kilde 1: How Many? Oversigt over antallet af fanger i Gulag fra 1930 til 1953

How Many?

According to widely published NKVD (hemmelige politi) documents, these were the numbers of prisoners in Gulag camps and colonies from 1930 to 1953, as counted on 1 January of each year:

| Year | Number of prisoners |

|---|---|

| 1930 | 179.000 |

| 1931 | 212.000 |

| 1932 | 268.700 |

| 1933 | 334.300 |

| 1934 | 510.307 |

| 1935 | 965.742 |

| 1936 | 1.296.494 |

| 1937 | 1.196.369 |

| 1938 | 1.881.570 |

| 1939 | 1.672.438 |

| 1940 | 1.659.992 |

| 1941 | 1.929.729 |

| 1942 | 1.777.043 |

| 1943 | 1.484.182 |

| 1944 | 1.179.819 |

| 1945 | 1.460.677 |

| 1946 | 1.703.093 |

| 1947 | 1.721.543 |

| 1948 | 2.199.535 |

| 1949 | 2.356.685 |

| 1950 | 2.561.351 |

| 1951 | 2.525.146 |

| 1952 | 2.504.514 |

| 1953 | 2.468.524 |

Kilde: Applebaum, Anne: Gulag - A History of the Soviet Camps, London 2003, side 516-516.

Kilde 2: Problemer ved brugen af angivelser af fangeantallet i Gulag

(…) Nevertheless, they (the numbers of prisoners) do not necessarily reflect the whole truth.

To begin with, the figures for each individual year are misleading, since they mask the camp system’s remarkably high turnover. In 1943, for example, 2.421.000 prisoners are recorded as having passed true the Gulag system, although the totals at the beginning and end of that year show a decline from 1.5 to 1.2 million. That number includes transfers within the system, but still indicates an enormous level of prisoner movement not reflected in the overall figures. By the same token, nearly a million prisoners left the camps during the war to join the Red Army, a fact which is barely reflected in the overall statistics, since so many prisoners arrived during the war years too. Another example: in 1947, 1.490.959 inmates entered the camps, and 1.012.967 left, an enormous turnover which is not reflected in the tables either.

Applebaum, Anne: Gulag - A History of the Soviet Camps, London 2003, side 516.

Formålet med Gulag

Kilde 1: NKVD cirkulære af 27. januar 1925, om udviklingen af arbejde i arbejdslejrområder

NKVD circular, January 27, 1925, on measures for developing work in areas of labor camps.

Circular No. 47

To Krai, Gunerniia, and Oblast’ inspectorates of places of incarceration

On steps to Develop Work Programs at Places of Incarceration.

The Corrective Labor Code defines our basic mission as assigning inmates to productive employment for the purpose of imparting the benefits of corrective labor to them.

In order to develop inmate employment, inmates should be organized as self-supporting work units exempt form all national and local taxes and levies (see Article 48 and 77 of the Corrective Labor Code).

In light of this acknowledgement of the importance of corrective labor for inmates, the aforementioned tax exemptions for the development of employment at places of incarceration, and the possibility of obtaining loans for the purpose of developing inmate employment, work programs must organized without fail at all places of incarceration in the RSFSR to the extent permitted by local conditions, and in exceptional cases officials may organize work programs that do not require substantial investments of fixed of liquid capital and at the same time would be open to participation by most of the inmates.

According to our information, it is obvious that work programs for inmates have not been organized at a large number of places of incarceration, thus depriving the inmates of the benefits of corrective labor, i.e., the places of incarceration are failing to accomplish their primary mission as defined by the Corrective Labor Code.

Deeming this to be improper and unacceptable, the Main Administration of Places of Incarceration believes that the organization of work programs is directly dependent on the energy and diligence of the guberniia Inspectorates of places of incarceration and recommends that you take additional steps immediately to organize work programs at all places of incarceration entrusted to you without exception and describe the progress of your efforts in your quarterly reports, to include the following information:

1) the names of the places of incarceration where work programs have been organized, the types of work programs organized, the number of inmates employed therein, the source and amount of funds for these programs; and

2) the names of the places of incarceration where work programs cannot be organized and the reasons why they cannot be organized.

In the process we should provide the following clarifications:

1) If any place of incarceration has any unencumbered and unused operating funds, these funds should be put to use be extending them as repayable loans to those places of incarceration where work programs could be instituted but have been held up solely because of a lack of funds;

2) Inspectors of Places of Incarceration are responsible for organizing work programs, and the progress of work program at places of incarceration shall constitute the yardstick for evaluating their performance and diligence.

Chief of the main administration of places of incarceration

(signed) Shirvindt

Head of the department of work programs and operations

(signed) Burlachenko

Kilde: Koenker, Diane P. og Bachman, Ronald P.: Revelations from the Russian Archives, Washington 1997, side 141-143.

Kilde 2: Rapport om en arbejdeslejr i Nizhni, Novgorod af 10. august 1932

Arbejdsspørgsmål

1. Hvad er siger kilde 1 om formålet med Gulag arbjedslejrene?

2. Hvordan lever lejren i Novgorod i følge kilde 2 op til kravene for en arbejdslejr?

3. Hvilker syn på fangerne i arbejdslejrene kommer til udtryk i kilde 1 og 2?

To the Presidium of VTsIK, Comrades Kiselyov and N Novikov,

To the Procurator of the RSFSR, Comrade Vyshinsky,

A Report On Conditions at the Penal Labor Colony in the City of Nizhni Novgorod.

The Nizhni Novgorod labor colony, built to accommodate eight hundred persons, had 3.461 persons incarcerated in it on 1 August 1932. The overload is explained, first by the fact that a lot of people are held for al long time under investigation and, second, by the fact that the people’s judges hearing cases apply the full force of the law (for example, for embezzling one hundred rubles or for swindling someone out of six rubles and so many kopecks or the like they give one or two years of strict solitary confinement) and, thirdly, by the fact that Moscow sends so many (there are instances of children being sent). The living accommodations look like the proverbial herring barrel packed with people. Iron bedsteads are _____ in number. Plank beds are furnished to _____ people, and the rest sleep on the bare floor. There are mattresses for only _______ persons in all, and no blankets or pillows. People sleep literally on bare plank beds. It’s dirty and stuffy in the place of confinement.

The practice of confining prisoners by category is not always precisely observed. A worker, peasant, kolkhoz member brought for the first time to the house of Coorection (Ispravdom) not infrequently finds himself among inveterate recidivises, prostitutes, and ruffians. For example, from rounds in the woman’s ward in one cell questioning reveled that here were repeat offenders and prostitutes with up to seven convictions, and here also were female factory workers and collective farmers with first convictions for stealing a goat or embezzling a hundred rubles, those still being investigated, and those simply taken into custody. During the inspection of the second ward, it became apparent that in cell no. 1 among working people deprived of their freedom were four repeat offenders. All newcomers to cell no.1 are subjected to a thorough search and under the threat of a knife have everything of any value whatsoever taken from then, not even mentioning the pieces of dried bread they bring with them, which as a rule are plucked by robbers immediately after they arrive. The administration views this outrageous situation with great indifference, and for this reason prevailing opinion among the prisoners is that it’s useless to complain. The head convict in the first ward, Razin, is a recid (recidivist thief), in the second ward, Lapshin, a recid, in the third, fourth, and fifth men convicted under paragraphs 162 and 193 of the Criminal Code (article 162 concerned theft; article 193, the last one in the 1926 Criminal Code, incorporated the 1924 Regulations on Crimes by Military Personnel)), in the sixth Rachkov, a recid convicted six times over, etc.

Prisoners communicate freely between cells; here too the possibility of theft is not absent.

At the House of Correction five oversight committees (comprising representatives of various bodies and social organizations who looked after the conditions of prisoners’ space) have been formed, their work goes on without proper leadership, committees’ sessions are very rarely attended by representatives of the Worker and Peasant Inspectorate, of Soviet social organizations, of the Gorsovet (Gorodskoi sovet, city council), Komsomol, and the Zhenotdel (Dhenskii otdel, the party’s woman’s section). At sessions up to eighty items are put up for consideration at one time. Oversight committee no. 3 may serve as an example. At the session of 1 July of this year, eighty-three items were considered; the session of 29 June considered eighty-six items. Using this approach, the work of an oversight committee becomes little more than pro forma, never going to the heart matters.

The House of Correction has three hundred staff; thirty-three of them are members of associate members of VKP (b), four Komsomol members. Of all the Communists, only one deals directly with prisoners and that in his capacity as secretary of the VKP(b) cell.

The political and educational work, the very core of the House of Corrections’ existence, is carried out very poorly. This work is killed by prison work activities and by inaction on the part of the administration. For 3.461 persons there are 760 newspaper subscriptions, 110 journal subscriptions. The club was designed for four hundred; 350 semiliterate persons are being taught. Vocational education was given to 263 persons in the first half of the year. The cultural service is wholly inadequate; it does not draw on the institutional and scientific strengths of Nizhni Novgorod. In their free time prisoners are pretty much left to their own devices. Observed were instances of card playing and telling of far-fetched stories hostile to the Soviet authorities.

Kilde: Sigelbaum, Lewis og Sokolov, Andrei: Stalinism as a Way of Life, Yale 2000, side 89-93.